On December 31, 1967, our son Bartek was born. One day after dinner, my stepfather, my mother, my wife Grazyna, and l were watching TV. On it was Comrade Gomulka, the First Secretary of the Party, saying that after Israel won the Six-Day War against the Soviet Union’s ally, Egypt.

Gomulka said that the fifth column of imperialistic Zionism appeared in Poland, and that Polish citizens of Jewish origin should now declare loyalty to the People’s Republic of Poland; if they don’t feel good here, then they can leave. Clad in the hands of the working class were banners that read in incomprehensible slogans: Zionists to Zion!”. lf I have to choose my homeland already;’ joked Polish-Jewish poet Antoni Slonimski, “why must it be Egypt'”?

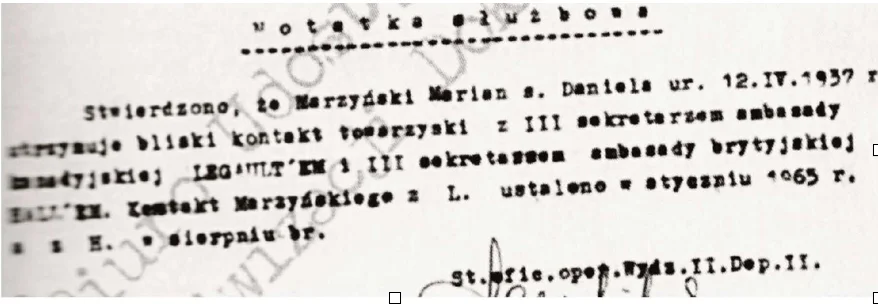

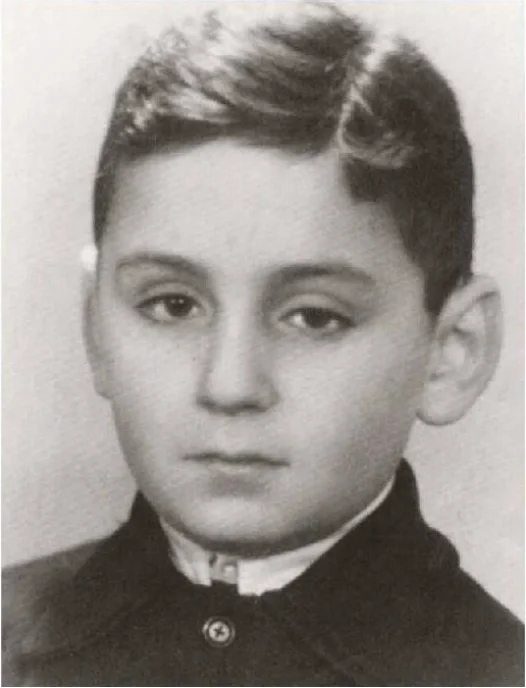

I was born in Warsaw in 1937, two and a half years before the Germans invaded Poland. War was my kindergarten. No playing house. My game was survival. In 1943, on the way to the concentration camp, my father cut a hole in train’s floor and jumped out to join the partisans. He was later killed in the forest.

My stepfather survived the war in a German officers’ camp; Grazyna spent the occupation in the village of Radom, where her father was paid in fresh butter and eggs for his surveyor work for farmers.

When the antisemitic campaign started in 1968 my mother and I were reminded of our imprisonment in the Warsaw Ghetto.

I recalled my escape to the Christian side in 1942 as a 5-year-old child: the horse and buggy, the crooks, the city police station, hiding in many apartments in Warsaw to avoid death, the baptism, my mother’s suicide attempt and being abandoned on the street. I remembered that I was smuggled out from the ghetto when a massive deportation of Jewish children had just started to the death

camps. I remember I had lost my parents, knew that I was a Jew but could not admit it.

At this moment we decided that our newborn should not live like us, in a lie.

Grazyna thought that we should head for the hills: “You shouldn’t be called Marzynski but Marzyciel [Dreamer], she said. “You may not understand the Polish anti-Semitism, but I remember what was said about the Jews in my neighborhood in Gdynia. lf we don’t get away from here, dear Marian, you will be crushed as easily as a fly on the wall”.

The antisemitic campaign soon started in full force. At first, we laughed. But later we saw the purge. Thousands of innocent people were losing their jobs. Television was staging anti-Semitic media events. We understood that the Jewish war was still on. Along with 15,000 others, we were closing the last chapter of Polish Jewry.

In the next few days, I was fired from at my job on Polish TV which put an end to my successful career. I ran in one breath to the third floor of what used to be a bank and was now TV headquarters. At the doors to the General Manager’s office, I encountered Comrade Tereska Modelska, his secretary. “The Director is waiting”, she said with a serious expression on her face – this coming from a woman who always was the first to laugh at my jokes.

“‘Well, every man must make his own in the world;’ said Comrade Stefanski, closing his eyelids. Then he added “we release you of your duties and we won’t air your finished broadcasts, but will pay you for them”.

The program director Lozinski was waiting behind the doors, came out and said to me, “Marian, you are the only Jew who I wouldn’t worry about telling an anti-Semitic joke to, and you’re leaving? Why?” I said to him, “Because l no longer what to be the Monument to the Unknown Jew.”

Following humiliating exit procedures and travel documents stating that we were not citizens of the Polish People’s Republic, we went to pick up a big crate that was meant to hold the few possessions I was allowed to take with me when leaving the country. The crate was addressed to Copenhagen. My parents came with us. And we started a new life.

(Source: Marian Marzynski, Life on Marz; Forgotten Exodus Project Interview)