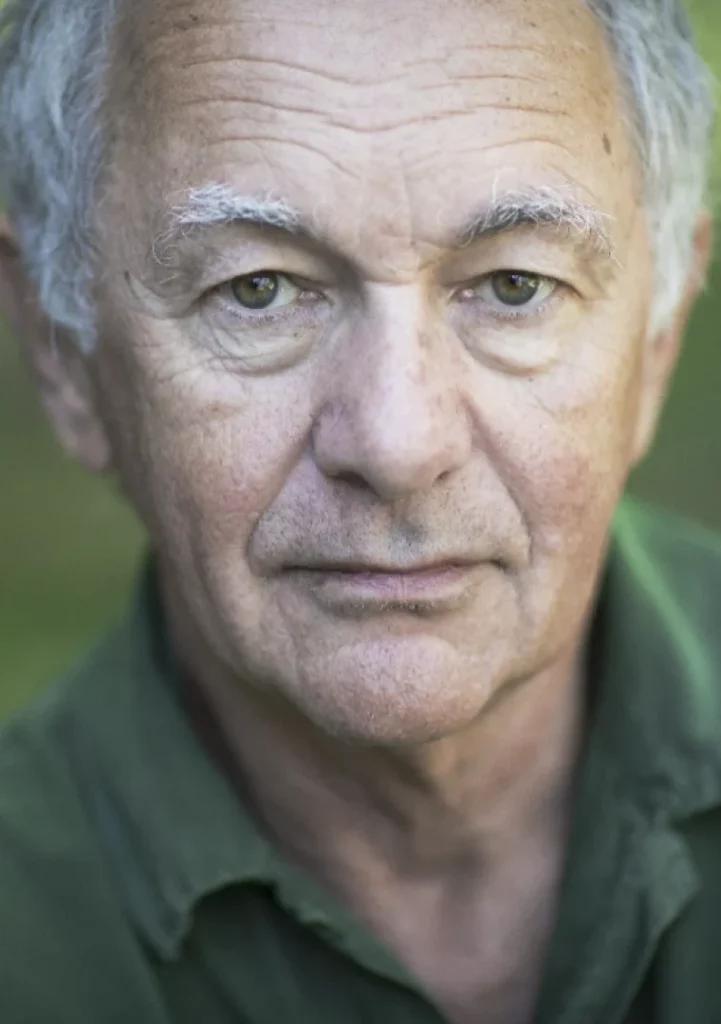

Born in 1951. Expelled from Poland in 1969.

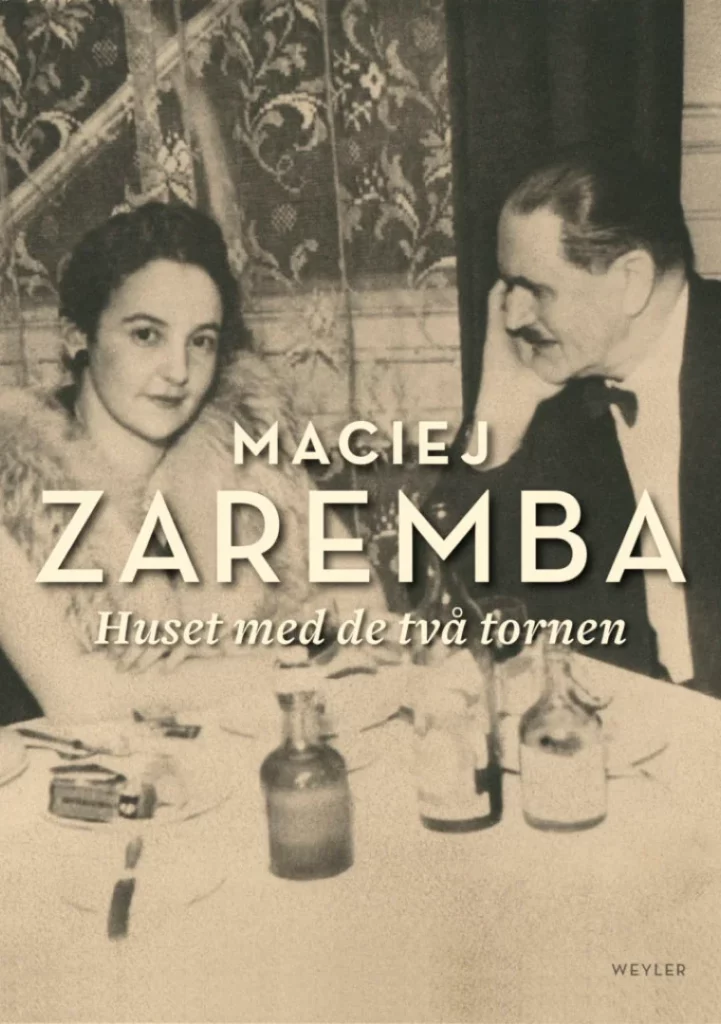

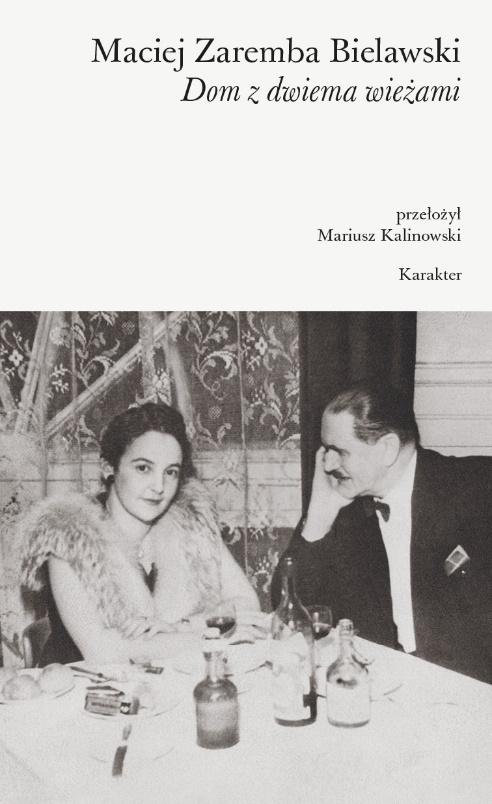

Excerpts from Huset med de två tornen (‘House with Two Towers’), Weyler, 2018. (Polish translation: Dom z dwiema wieżami, Karakter, 2018).

I shall try to recreate the prevailing atmosphere, to understand why he – now I – isn’t shocked when the Party starts persecuting Jews. Initially, he doesn’t grasp that it is Jews they are targeting. He doesn’t know what “Zionists” are. No one can keep up with the number of the enemies that beset the ruling system. If it’s not CIA imperialists (who release Colorado beetles over the fields, which accounts for the shortage of potatoes), then it’s German revanchists lurking at the border, supported by fascists, racists, capitalists and colonialists, along with their local lackeys: Trotskyists, revisionists, anarcho-syndicalists, Thomists, voluntarists, symbolists, reformists, formalists, freemasons and idealists.

“They’ve left out cyclists,” the people in the streets mutter.

And when it finally dawns on him that “Zionist” means “Jew”, he doesn’t grasp what an outrage this is.

As far as he can see, it’s impossible for Poland’s communists to betray their ideology, for they have none. They are just a bunch of camp followers. The old communists, those who were shot on Stalin’s orders – they believed in their utopia. The new ones don’t believe in anything. And because no one believes what they say either, it matters little if it is “Jews” who are currently being scapegoated for the fact that nothing works. Everyone knows anyway that the fault lies with the system.

I believe that’s how he thinks. Maybe he’s even a little proud of his clear-sightedness. He shrugs. He has no illusions. He is ignorant of history and does not hear the howling of demons being released.

December 1968. Mama comes into my room. She asks me to sit down. She has something to tell me.

Wyjeżdżamy. Jestem Żydówką.

In Polish, the message is just three words long. “We have to leave. I’m a Jew.”

A second passes and I hear myself say, “Of course, dear Mama. We have to leave.”

It is only now, fifty years on, that I can fully understand the fear she feels on opening the door to my room. She cannot know what ideas I have about Jews. The topic is a non-subject in our family. What I don’t know is that her fear is now in its seventh month. In March, the Party orders her to dismiss four people claimed to be of Jewish descent. When she doesn’t obey, they demand that she submit a description of her life history. When she refuses to do that either, she is told that it may be dangerous to walk alone through the hospital park. Then someone punctures the fuel hose in the car allocated to her for work. An observant mechanic discovers the damage in time.

Comrade Gomułka’s people are making sure that the country’s last Jews will never forget the last stage of their time in Poland. It’s unclear whether there is a plan, or whether they are relying on existing tradition. But rumors spread that those who are emigrating are being charged for their studies, and that their diplomas and documentary proof of completed studies can be seized at customs. What is indisputable is that emigrants need authorization for every single item they want to take with them, down to their last sock, pen and napkin. In principle, objects more than thirty years old are not allowed out of the country.

At the local Education Authority, I’m supposed to get a stamp to certify that my school-leaving certificate is genuine.

At the National Education Authority, a further stamp is required to certify that the first one is trustworthy. And then a third one to guarantee the reliability of the two others. Three separate authorities, three waiting rooms, three stamp fees. The same procedure for Mama’s diplomas, and a further one to have the English translation authenticated, confirmed and witnessed. The stamps are so large that they won’t fit on the documents, so the latter have to be extended; a functionary attaches a new sheet of paper, there’s a stamp to seal the join, a further fee. Inside, there’s nearly always the same stage set. Brown wooden panels, a desk, glasses of tea, a secretary; no, the section head is in a meeting, come back tomorrow, oh, wait – no, he’ll be away all week, come back next Monday.

She looks up, relishing the effect this has. On one occasion I nearly slip out of my allotted role. Paintings by Mama’s maternal uncle Emil are not allowed out of the country. They are part of Poland’s cultural heritage, the civil servant working for the head of the national authority for antiquities informs me. It’s on the tip of my tongue to say that if the head of that authority were to root around in the mass graves, he’d find more cultural heritage. Emil Schinagel was murdered by Germans, but betrayed by Poles. So maybe his gold fillings are Polish property too?

Was it at the Ministry of Education? A buxom peroxide blonde with heavy kohl eyeliner stiffens when she hears what I’ve come for. “Please leave your papers here and wait outside.” A quarter of an hour later she comes out with a black look on her face, ignores the other people waiting, comes up to me. She is breathing heavily, as if after a performance. “Here you are, everything’s been dealt with now. May God in His mercy forgive those swine.” I want to say something, but I can tell from her demeanor that I’d better not. I bow and go out without looking back.

Sometimes the emigrants are asked how they remember the country they left behind. For me, it’s always been her. A peroxide blonde with sweat patches under her arms and melting makeup. She is my Poland. Not weeping willows, not even Chopin.

Translation from Swedish: Fiona Graham