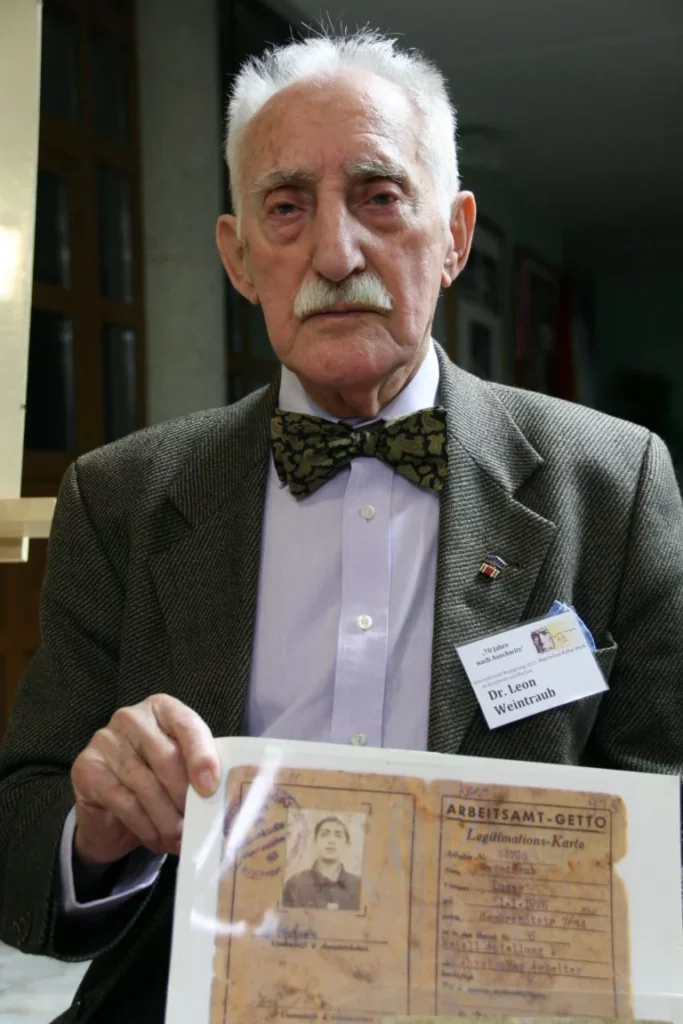

Pre-War Life in Poland

I was born in the Polish town of Łódź on January 1st, 1926. Despite living in poverty, I had a peaceful childhood. When the Wehrmacht invaded our town on September 8th, 1939, life changed drastically.

As a Jew, I was subject to restrictions, including a curfew that required me to be indoors after 6 pm, and the confiscation of any valuables. In less than a week, the mayor of Łódź publicly announced the creation of a Jewish ghetto, referring to our community as a “plague” that needed to be eradicated.

There may have been moments in your life when you were too occupied to find time for meals during the day. However, what you felt pales in comparison to what I experienced for nearly six years. From September 1939 to around April 20th, 1945, I endured an unrelenting hunger that persisted for five years, seven months, and three weeks. I was hungry, hungry, and hungry.

Deportation to Auschwitz

During the spring of 1944, word spread that the Red Army was approaching the Vistula River, near Warsaw. German officials were growing anxious about the front line drawing nearer. On August 18th, they summoned us to gather at the Umschlagplatz, a collection site located near the train station for deportations from the Ghetto.

The following morning, a train arrived to deport us, and we were loaded into cramped cattle wagons. The experience was a jolt to our senses. The doors were shut, and the train began its journey of horror, which spanned days and nights, without any food or water. The conditions were inhuman.

Eventually, the train stopped one morning, and the doors were flung open. We were greeted by people wearing striped, pajama-like clothes, shouting “Raus! Raus!” which translates to “Out!”

As I bid farewell to my mother, I couldn’t help but notice how young she looked. She was wearing a dark blue suit, a white blouse, and a hint of rouge on her cheeks. With conviction, I shouted, “We will reunite inside!”. It turned out to be the last time I saw her.

The process of dehumanization continued. They wanted to transform us into instruments that were only useful as long as we could work, and were disposed of once we became useless. They directed us to a shower area and confiscated all our belongings. We were scrubbed with a terrible smelling disinfectant before being given prisoner uniforms. Finally, we were led to another building known as a block.

Life in Auschwitz

One day, near the end of September, I saw a group of naked men while walking between the blocks. After some hesitation, I dared to ask them why they were naked. They told me that they had been registered, branded with tattooed prisoner numbers, and were waiting for new clothes before being transported to work outside of Auschwitz.

At that juncture, there were no kapos or SS officers in sight. So, I took off my clothes and sneaked into the group. I can thank my lucky star, because the kapos and SS men did not find out that I was not registered with that group.

They never told us when or where they would take us, only to find ourselves at Döhrnau – a subsidiary of the Groß-Rosen Concentration Camp in Germany.

As an electrician I was put to slave labor, responsible for the construction of underground weapon factories, known as ‘Projekt Riese’.

Death March and Deportation to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp

During the 1950s, I obtained documentation from the Red Cross that I had been deported to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp on February 25th, 1945. The journey began with a grueling death march in the middle of February, as I marched through bitter cold snow, surrounded by other prisoners. After three days, we finally arrived at Flossenbürg, where we were met with nothing but cold, starvation, and death.

The Liberation

One day, we were taken to the train station and loaded into regular trains instead of the usual cattle wagons. After arriving in the German Black Forest, the guards unexpectedly disappeared, prompting us to march in the opposite direction until we stumbled upon a town called Donaueschingen the following morning.

I was fortunate enough to see a doctor who informed me that I had contracted typhoid fever, and was admitted to the hospital. During my stay, I became delirious and lost consciousness, weighing only 35 kilos at the age of 19.

Upon regaining consciousness, I found myself completely lost and with no one to turn to for guidance or support. As I stood there, a passerby recognized me as a former concentration camp prisoner and told me about a group of survivors living in a nearby village. I found my way to Konstanz, a town on the Swiss-German border, where I was admitted to a sanatorium. There, I was able to go to a big library and started to read, read, and read.

Starting a new life in Poland

After the end of the war, I wanted to do something with my life and continue my education.

Fortunately, the British Occupation Army had reserved spaces at universities for Holocaust survivors, and I was able to secure one. Despite the dean’s attempts to discourage me from studying medicine in a foreign language with only six grades of pre-war education, I remained determined and ultimately succeeded in passing my exams across all medical disciplines.

In October 1950, I relocated to Warsaw, with my family joining me in April of the following year. I was employed as a doctor at a clinic specializing in women’s diseases and obstetrics. After completing my dissertation in January 1966, I was appointed chief of staff and enjoyed three years of great happiness in the position.

Expelled from Poland in 1968

In 1968, I attended an endocrinology congress in Łódź with a team of doctors from the hospital in Otwock where I was working. We presented a number of scientific papers, which were met with high praise from the Scientific Council of the Ministry of Health.

Unfortunately, our success was short-lived. A few days later, we received a letter from Dr. Władysław Pasławski, the head of the district health department in Otwock, which placed restrictions on our work. These included bans on scientific research and on the use of X-rays in our treatment of patients, and an order to review all medical records related to our work.

I was surprised by this sudden change in attitude, as Dr. Pasławski had been very supportive of our work. In response, I wrote letters to various high-ranking officials, including the Minister of Health, to challenge the restrictions.

My efforts proved to be useless. I was summoned to a hearing in February 1969 by the district committee of the Polish Workers’ Party (PZPR) where I was accused of abusing my power as a ward doctor. It was apparent that the reason for the accusation was due to my Jewish background and the ongoing antisemitic campaign.

The hospital director, Dr. Stanisław Oracz, was punished with a party reprimand for supporting me. I received a three-month notice from my job and was dismissed.

The nurse supervisor approached me with an offer to collect signatures from staff defending me. I declined her offer, warning her that she might only end up hurting herself. After packing my belongings and tidying up my office, I left the hospital for good.

At this juncture I was thinking about how I had returned to Poland to build my country and was now forced to leave. The reality of my situation came as a surprise, as I had never given much thought to my Jewish identity or how it set me apart from others. To me, I was simply a doctor whose patients depended on my expertise, and I felt respected by them in turn. Even when treating patients who may have held anti-Semitic views, they never made it apparent, and I never felt inferior to them.

Even when the newspapers were filled with anti-Jewish articles, I didn’t think it applied to me. I felt as a Pole, a full citizen of my country, I was helping people, saving their lives, fulfilling my function. I had a good opinion about myself. If others had a different opinion, as my eldest sister Lola used to say, it wasn’t your problem, it was theirs.

The antisemitic campaign that resulted in our departure from Poland was deeply painful. It shattered my positive self-image and left me feeling disappointed and hurt. From eighty members of my family, only sixteen – one of five – had survived the horrors of the Holocaust. I believed that we had already paid a heavy price for simply being who we were.

I was thinking about where to go next. Going back to Germany was not an option, and moving to Israel during a time of war was not desirable since I didn’t want any more family members to get killed.

I decided to emigrate to a neutral country, Sweden, which needed obstetrician-gynecologists and welcomed us with open arms.

On September 1st, 1969 – exactly thirty years after the start of World War Two – we crossed the border to Germany before continuing our journey to Sweden. After four months of arrival, I started working as a doctor, quickly picked up the Swedish language and started a new life in the country.

Remember Lessons from the Past

We need to remember the past to learn from history. As a surgeon, I can attest that regardless of skin color, the tissues and organs beneath the skin are identical in all people. The idea of race is a myth; DNA science has confirmed that Homo sapiens is the only race, and all racist ideologies were founded on a flawed premise.

Babies are born without prejudice or opinions, and as humans, we should strive to remain that way until death. I consider myself a Survivor, not a victim. My family members who perished during the Holocaust were victims. I take pride in being alive and sharing my understanding of the dangers of homophobia, racism, antisemitism, and Nazism.

I am 97 years old today. There is a four-letter word that I removed from my vocabulary: the word that starts with “H” and ends with “E.” This word has caused immense harm to humanity. I also stopped using the word “revenge.” I do not want to inflict upon others what was done to me. While I cannot forgive, I believe reconciliation is the word we should use to end the cycle of evil.

(Source: Forgotten Exodus Project Interview, Minority Rights)