My father was born in 1910, in Zamosc; my mother was born five years later in Lublin—both to traditionally religious families. At this time, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world—3 million souls—and a principal center of Jewish culture.

Like many young Polish Jews who rebelled against their traditional upbringing by joining radical social and political organizations, my father joined the Communist Party in his early teens. He was imprisoned after involvement in a number of Party actions.

My parents moved in together in May 1939; the war broke out in September. They fled from a devastatingly bombarded Warsaw on foot, wandering around different towns and villages until they reached the Soviet border. In June 1940 my parents were arrested by the Russian secret police, the NKVD, and deported to a Gulag. During their arrest, my mother asked the Soviet officer what they would do to them. He replied that “You will be sent to a place where the birds can’t reach”.

Arriving in Siberia, they had to build their barracks with their own bare hands. My mother said that people were dying like flies due to inhuman working conditions and chronic food shortages.

There was a cemetery in front of their barracks where huge fires were burned to warm up the frozen land so that they could dig graves for inmates who had starved to death.

In 1946, after their liberation, they made their way back to Poland by a 40-day train journey, in cattle cars, together with my brother who had been born during a temporary stay in central Asia.

Ragged and tattered, using canned-food tins for cooking pots, dressed in scraps of blankets instead of coats – they arrived in the city of Wrocław in the spring of 1946 with other Jewish survivors. The locals stared at them, amazed that they had survived the war. This was when my parents found out that all of their family members who had stayed in Poland – including parents, siblings, and cousins – had been murdered during the Holocaust. They were the sole survivors.

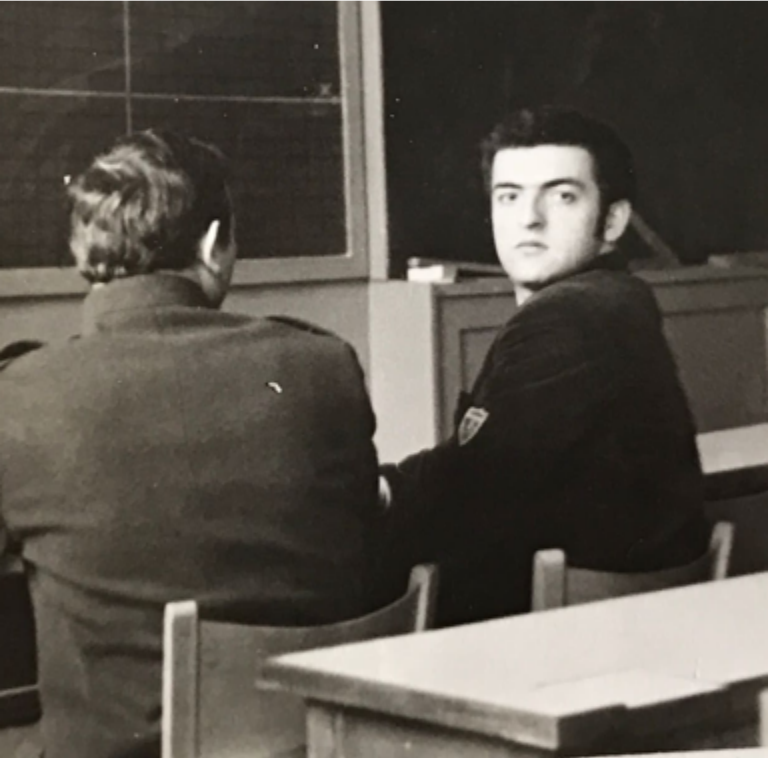

Looking for pre-war friends and finding both Zamosc and Lublin hostile to and bereft of Jews, they eventually moved to Katowice where I was born in 1950. In 1968, I entered as a freshman studying sociology at the Jagiellonian University, while my brother was enrolled at Krakow University. We both took part in activities of the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKZ).

Then came March 1968, which became a turning point in our life. I remember sitting at home and watching TV when the First Secretary of the Communist Party, Władysław Gomułka, said that Jews were a “fifth column” and called for our expulsion from the country.

The return of Polish antisemitism felt like a slap in my face. It became evident that the authorities wanted the country to become “judenrein” through a systematic campaign of harassment. My parents – and many of their friends – were targeted at work and started to re-experience their traumatic wartime memories of persecution. This led to an intense debate at home: should we stay or leave?

Having been fully integrated into society, and having mainly Polish friends, it was particularly distressing that most of my acquaintances were indifferent to our plight. The lack of empathy from those around us further fueled my desire to leave Poland and build a new life free from antisemitism. The pervasive anti-Jewish sentiment had become unbearable, and I was determined to start afresh in a place where I could build a life in freedom, free from persecution.

I went to the authorities on my own initiative, applied for permission to leave the country and was unexpectedly issued a tourist passport. I took the train to Paris in June 1969, where I stayed with family members. After a three-month stay in France, I immigrated to Sweden, where I was joined by my parents and the rest of my family in 1970. We built a new life here, enjoying the fruits of liberty without the burden of oppression.

There is a saying that the one who does not remember history is doomed to repeat it. Today we once again experience an increase of antisemitism globally – often under the disguise of anti-Zionism. We need to fight it before it’s too late.

(Source: Forgotten Exodus Interview)