My father Adam Bromberg, like many Polish Jews, was a communist before the Second World War. He was imprisoned for many years for his views. Then came the war, and as an officer in a Polish division of the Russian army, he helped liberate Poland from the Germans. While fighting for Poland’s liberation, his entire family was wiped out by the Nazi occupiers. He and his niece Gabriella were the only survivors of his large family.

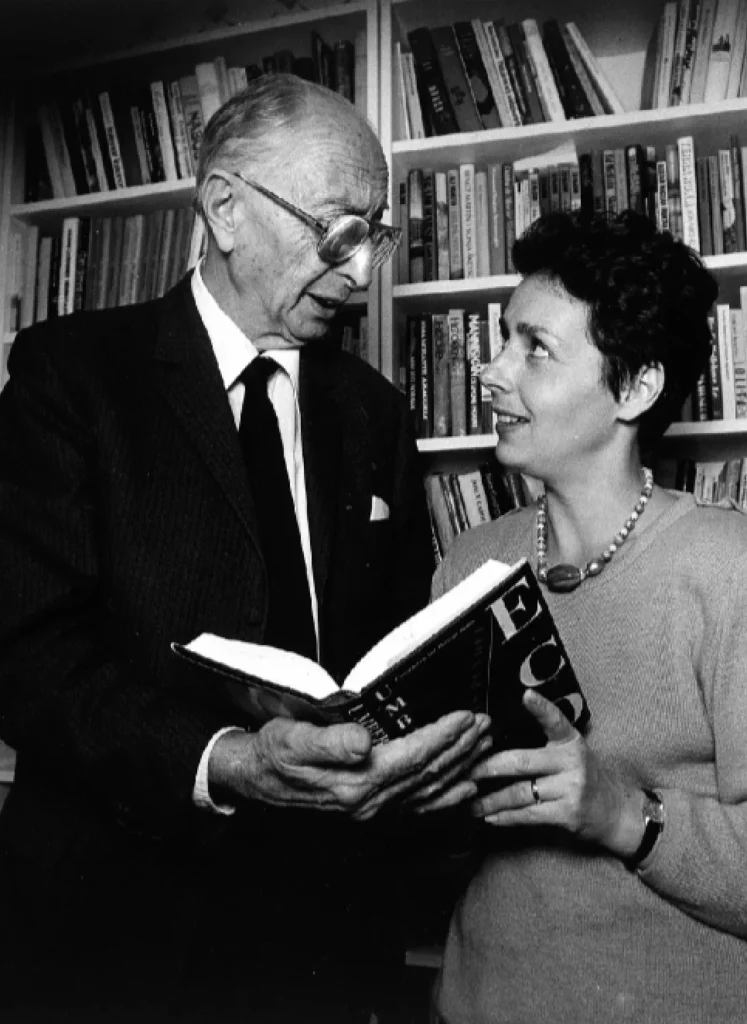

After the war, my father enthusiastically participated in the reconstruction of the new Poland—which, he believed, would never again allow persecution and discrimination. He founded several book publishing companies, including PWN, which became one of the world’s largest scientific book publishers.

My mother Anna was a scientist, and my parents had a rich social life in Warsaw. They felt primarily Polish. Poles of Jewish origin. Their respective relatives were fully assimilated bourgeois Jews in Lwów and Lublin since the 17th century. But it soon turned out that it didn’t matter how assimilated they felt. Their blood was never Polish enough.

March 8, 1968, was a turning point in our family’s safe and orderly life. I was 15 years old and on that fateful day I was at the University of Warsaw. Suddenly I heard something in the street: a small group of students were demonstrating outside the university building. They were immediately met by police officers who beat them indiscriminately and used tear gas. Terrible scenes unfolded before my eyes. An elderly man was caught in the middle of the commotion. In honor of Women’s Day, he had a bunch of red roses in his arms. He was beaten to pieces – there he lay in a pool of blood with the red roses scattered around him.

Panic broke out, people screamed and ran in all directions. Terrified, I ran home. I remember the fear, the frenzied violence that I saw for the first time in my life.

Everything that happened after that I remember as in a fog, like a bad dream.

The next day we could read in the newspapers and hear on radio and TV that it was Jews (“Zionists”) who had incited the students. On the same day, my father was stripped of all his duties. He lost his job—was made redundant as a newspaper columnist and university lecturer. The regime’s strategy was clear: the Jews would be blamed for everything that was wrong with the country.

Almost all our friends and acquaintances disappeared. We were forced out of the home where we had lived for over twenty years. We had to move to a small apartment in a house where the neighbors openly distanced themselves from us.

One day we read on our front door that it was a pity Hitler hadn’t finished his job. The second day the door handles were screwed off, the next day there were threatening letters in our mailbox. It often happened that on my way to school I had some of the neighborhood boys following me. They amused themselves by describing in detail how they would rape me.

At school, everything changed. Before 8th of March, I had many friends and I had top marks in all subjects. Suddenly all my friends were gone, no one dared to talk to me anymore. My grades were lowered. No matter how much I read and prepared, I got the lowest marks with the explanation that Jews deserved no better.

As if it wasn’t enough that I had lost my best friend, I was accused of causing her death. The school reported me to the police, and forced me to confess my “crime” in front of all the students in the auditorium.

Our family found it increasingly difficult. After a major media campaign against my father, he was threatened with prosecution, accused of involvement in “a Zionist conspiracy” against Poland. His sentence would be ten years or life imprisonment. He spent nights writing his own defense speech as he was not allowed his own lawyer. He was detained and interrogated more or less daily for a year. Over a hundred witnesses were forced to sign false testimonies against him.

Now we had no income, no chance to get a job, no money left, and we had to sell everything of value. The situation became untenable, and we applied for an exit permit.

One rejection followed another. In the end, we were told that we would never be allowed to leave Poland, that my father would be sentenced and imprisoned for many years to come. At the same time, my older sister Maja got permission to travel abroad. They wanted to harass us further by breaking up the family.

One day, without any warning, the rest of the family also received an exit permit. We never hesitated. On a beautiful August day in 1970 we boarded the boat to Ystad. Not until we were on Swedish soil did we dare to realize that the nightmare was over. The only thought we carried with us then was: never again, never again. Whatever would happen in the new, unknown Sweden, we would never have to experience anything like this again. No more antisemitism!

(Source: Swedish Jewish Museum)