My mother grew up in an impoverished, deeply religious family in Lodz. My father, who comes from a more assimilated family, recounted experiencing anti-Semitism in pre-war Poland, including being denied job opportunities due to his Jewish background, and facing physical violence. Due to these challenges, he was drawn to the concept of Israel and became a member of Hashomer Hatzair, a secular youth movement rooted in labor-Zionism that he joined while in Lodz and where he eventually met my mother.

My father and his siblings struggled to find consistent work, prompting them to take out loans from my grandmother to establish a small fabric production company in 1938-1939. The onset of the Second World War disrupted their business and drastically altered their lives.

Following the German occupation, my parents quickly became aware of the anti-semitic restrictions. Jews were humiliated, forbidden to walk on sidewalks, were beaten and got their belongings confiscated. It became apparent that a dangerous future lay ahead. As a result, my parents made the decision to escape to the parts of Poland that were under Soviet control.

When they arrived at the station, a large police operation was underway. Their Jewish identity was evident, particularly due to my mother’s appearance. As a result, they had to return home and wait a few days before attempting to flee again. As Jews were not permitted to purchase train tickets, they had to hide in the toilet stalls on the train.

After enduring a treacherous journey, characterized by, filth, and cold, they finally arrived in Lviv.

They utilized their contacts to secure housing and employment, but there were rumors circulating that Stalin’s Secret Policy, the NKVD, would soon capture and deport illegal refugees like themselves to Siberia. They were ultimately arrested and deported. Paradoxically, it was this forced relocation to a remote Siberian village that ultimately saved their lives, as Jews who remained were executed in the forests in a gruesome campaign known as the “Holocaust by bullets.” My parents were imprisoned in Siberia until their release in 1942 when they went to Uzbekistan, where they remained until the war’s conclusion. They proudly rejected Soviet citizenship and began making preparations to return to Poland, despite having no knowledge of the situation there.

Upon arrival in Lodz, my parents headed to the apartment in the former Ghetto where my maternal grandparents had lived. The place was a mess with garbage strewn across the floor. It seemed as though someone had left in haste. As they looked around, they stumbled upon a few old family photographs amidst the trash, but that was all they could find. Despite searching high and low for any trace of their relatives, they came up empty-handed. The future appeared to be grim.

Life in Poland before the anti-Semitic campaign of 1968

After relocating to Warsaw, my mother reunited with her surviving sisters, and in 1947, we received news that my father’s brother, Jacob, had survived both the Lodz Ghetto, Auschwitz and forced labor in Germany. Eventually liberated by the British, he was discovered in a debilitated state weighing under 40 kilograms and suffering from typhoid fever. Jacob held the belief that Jews should leave Poland. However, my family decided to remain in Poland due to my father’s employment.

Around 1949, my father secured a managerial position at GAL, a prominent shipping company, and we settled into a luxurious villa with a beautiful garden, aided by our housekeeper Janina.

Suddenly, my father became a high-ranking official in the communist hierarchy.

To hide our Jewish background, my family was ordered to change their name from Zilberstein to a Polish-sounding name. My father told me that his only attempt of resistance consisted in choosing the name Sarnecki in memory of his mother Sara, who had been murdered by the Nazis. However, the onset of de-Stalinization in the 1950s leads to persecution of Jews, and Dad’s safety was threatened due to conflict between Communist Party factions. He became the manager of a Polish-Chinese shipping company, prompting our family to relocate to Tientsin, China.

Antisemitism in 1956

In 1956, the rise in anti-Semitism led to many Jews leaving Poland. During a holiday in Warsaw, a woman asked me if we were leaving too, prompting my mother to disclose that we too were Jewish. This was a challenging revelation as I was already aware of the negative connotations of being Jewish, making it hard to fit in. Discovering that my older cousin shared the same background eased the struggle.

When my family returned to Poland from China after my mother’s pregnancy, we experienced a noticeable shift in the political climate, causing my dad to lose his job and face unfounded accusations. Our financial situation became strained.

Expulsion from Poland in 1968

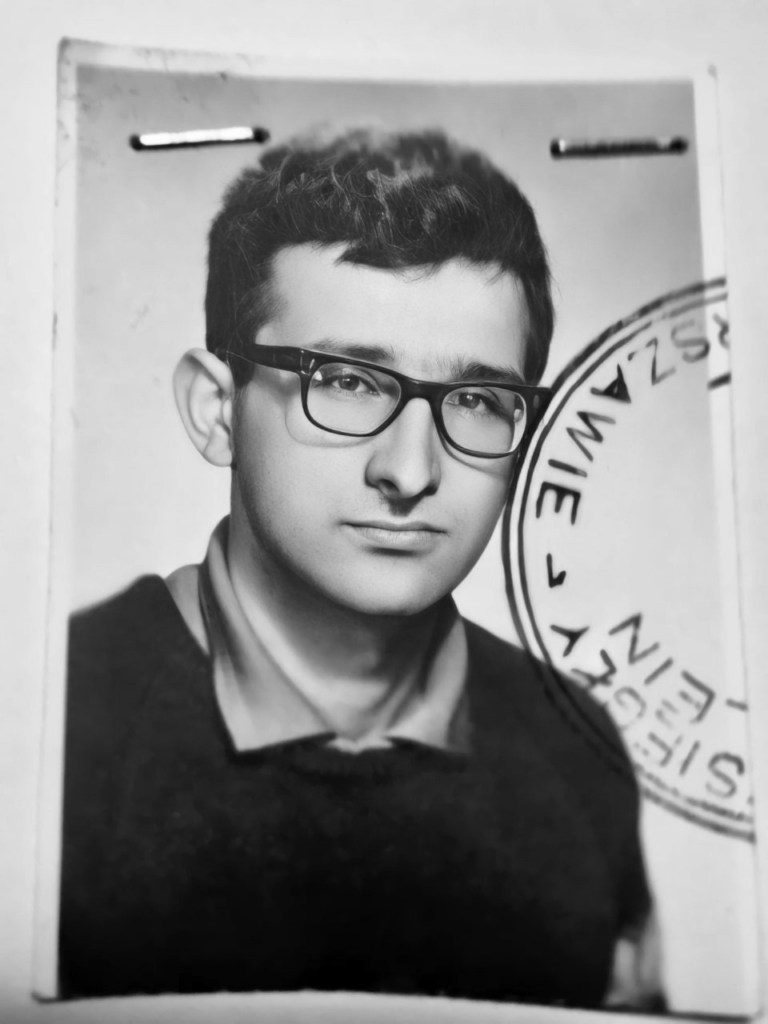

In 1967, I remember arriving home from The University of Technology where I studied to find my mother in tears. When I asked what had happened, she told me about the war in Israel. At the time, I didn’t fully comprehend its significance, but I realized that my parents’ connection to Israel was stronger than I had known. After that, things just got worse at a lightning speed.

After the events of March 1968, my father lost his job a second time. The anti-Semitic campaign intensified, and my family had to leave Poland. We had no livelihood and heard rumors of barracks being built to intern Jews. We all understood we could not stay. I was 21 years old and didn’t want to leave. However, I couldn’t let my parents and younger sister leave the country without me.

This was a traumatic experience for me as I had never imagined having to leave my home and adjust to a new language, culture, and friends. I remember an immense feeling of sadness and depression in the first few months of our journey. We traveled to Vienna, Rome, and eventually reached Sweden.

New life in Sweden

Sweden was the only country that offered to take my family in. Upon arrival in Malmö, we were taken to a washing and disinfecting facility, where we had to strip naked and get into showers. Survivors from Auschwitz were present, making it a challenging experience.

We were then transported to a camp in Lidköping where we spent the summer of 1969. Although we lived in modest barracks, we enjoyed the beautiful surroundings and had the opportunity to learn Swedish. The summer of 1969 came to be known as the summer of the century. We thought we had come to paradise.

After a time of mourning for my lost life, I found it quite easy to let go of the past and embrace new opportunities. It was a fantastic feeling to have a fresh start and the chance to build a better life. However, the experience was different for my parents. They were older and struggled with the language, and the challenges of starting all over again.

My parents eventually found work, and we moved to Stockholm, where settled in Täby and found vibrant Polish-Jewish community. As a result, it felt like my parents had ended up in a small, tight-knit shtetl. The participated in activities like bridge games and walks, but there were also inevitable funerals for members of the community.

I consider myself as a Swedish, culturally non-religious Jew. There are ample anti-Semites that serve as a constant reminder of my heritage, even if I were to forget it. While I have good friends in Poland, I am not Polish in any way.

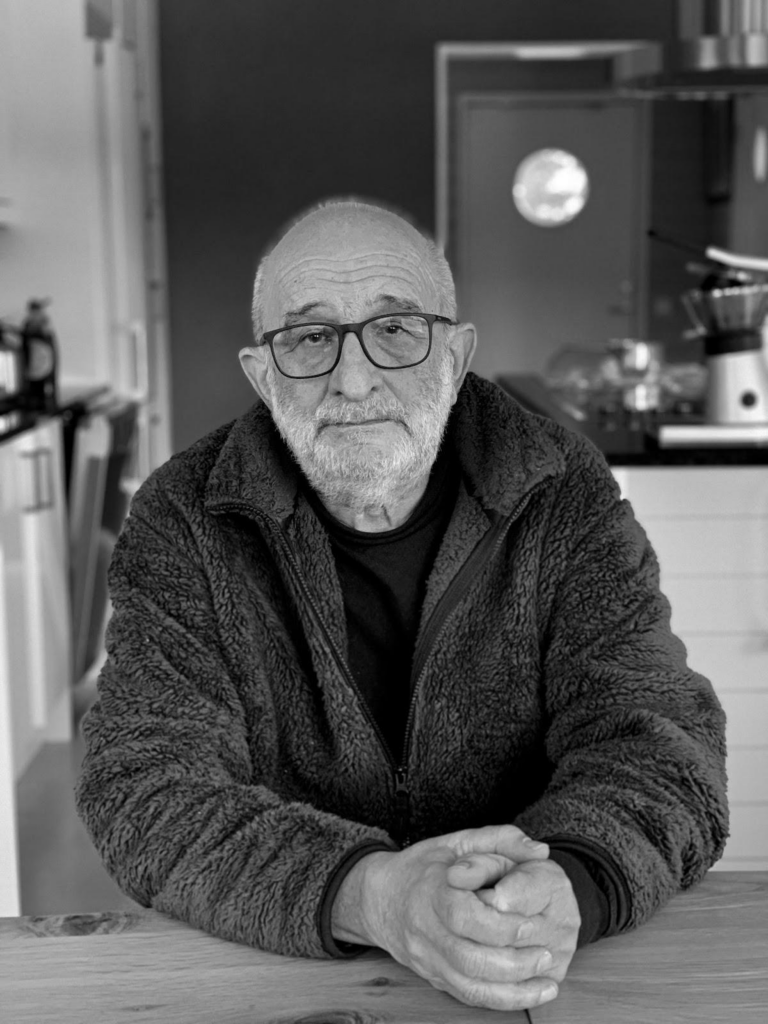

Although we have now lived in Sweden for a long time, I still encounter anti-Semitism as a well-known public figure and academic, especially on various pages on the Internet and in the form of emails I receive. I often remind my children that we come from a family that has had to flee multiple times, and that anything is possible in the current world.

Many years ago, when I was newly appointed professor of criminology at Stockholm University, I was invited to deliver a lecture in Polish at the most prestigious hall of Warsaw University. The speaker introduced me as “Professor Jerzy Sarnecki from Sweden, who could have been a professor here but was forced to leave the country due to the antisemitic campaign 1968.” Although it is not accurate that I could have become a professor in Poland due to my dyslexia, this was a very strong experience despite all the years in Sweden and all humiliation we suffered in 1968.

(Source: Forgotten Exodus Interview)