Dr. Dariusz Stola

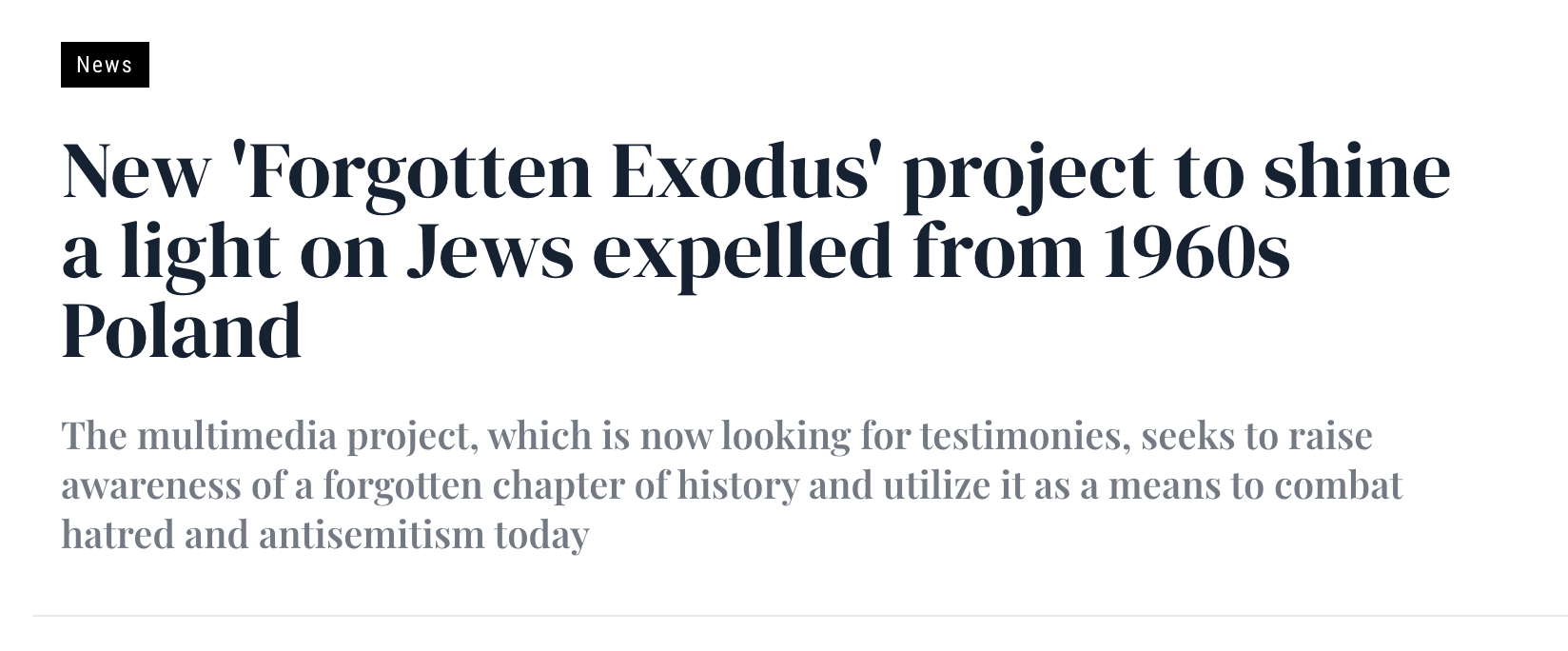

In Polish historiography the dramatic events of spring 1968 are often simply referred to as ‘March’, and for many people the term is synonymous with an anti-Jewish witch-hunt. The witch-hunt’s official name was “anti-Zionist campaign”. I place the terms Zionism and Zionists in italics as they belong neither to Polish nor English but to another language: the Orwellian newspeak of the Communist Party. They were not used to refer to a particular variety of nationalism, but were substitutes for ‘Jew’ and ‘Jewish’, including cases where the person referred to as a Zionist was neither Jewish nor pro-Israeli.

The hate campaign that began in March 1968 included aggressive antisemitic propaganda—barely covered with the fig leaf of anti-Zionism; mass mobilization against “the enemies of socialist Poland”, among whom the Zionists stood prominently; expulsion of Jews from the party, govern- ment posts, and other positions; the destruction or drastic restriction Jewish institutions and organizations; and discrimination against and harassment of individuals for being Jewish. Last but not least, the wave of Jewish emigration that followed the campaign (encouraged, induced, sometimes simply forced by the authorities) reduced the Jewish population in Poland by half and brought organized Jewish life to the edge of extinction.

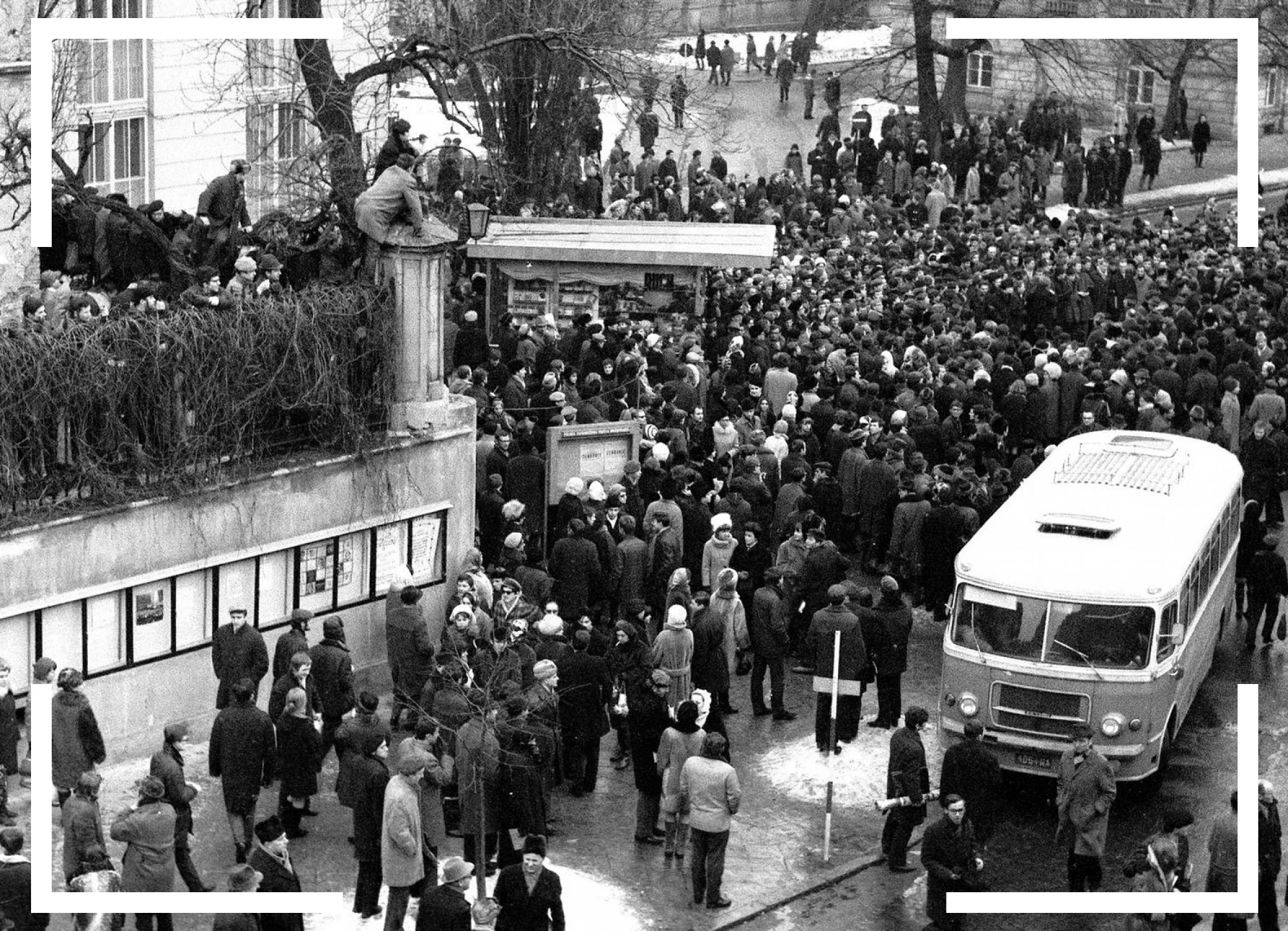

The anti-Zionist campaign was secondary to the main chapter of the March events: a youth rebellion and its pacification by the authorities. Street riots broke out when police and groups of the Communist Party aktyw armed with clubs brutally attacked a peaceful student rally at Warsaw University on 8 March. In the days following in Warsaw and other academic centres there were numerous protest meetings, student strikes, and street riots, to which the authorities responded with police clubs, arrests, expulsions from the universities, and conscription into the army. While students were the primary agents of the rebellion, protests also took place in cities without academic institutions (in more than a hundred localities across Poland) and involved many young workers and secondary school students. By 27 March the police had arrested 2,591 people, including 597 students, while more than 600 students had been drafted into the army and sent to distant garrisons. Many more people were beaten, removed from universities, blacklisted by the secret police, and made the object of various other forms of harassment. Repression continued for the next few months, but key leaders of the protest were kept behind bars till the amnesty of 1969, and two of them: Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski, remained imprisoned up to 1971.

A related current of the events was the attack against dissident intellectuals, including persecution of independent-minded writers (favoured targets were the Catholic writers Paweł Jasienica and Stefan Kisielewski), scholars, and artists, which evolved into a wider campaign of intimidation of the intelligentsia. Thus, the Zionists were under fire in a peculiar company of young rioters, Catholic intellectuals, and independent artists. The third current, least visible but key for the development of the events, was a power struggle between party factions, groups, and leaders that went on behind the scenes. To make sure, no proof of any Zionist conspiracy behind the youth rebellion of 1968 or the faction struggle has been ever found. The claim was one of the factors endowing the campaign with its grotesque character.

On the eve of the campaign Polish Jews were a small relic of the once great Polish Jewry. There were approximately 25,000–30,000 Jews among Poland’s 32 million inhabitants (i.e. no more than 0.01 per cent). The group was aging, its Yiddish culture and religion in retreat. The group’s education levels were well above the rest of the population, which meant that they were strongly overrepresented among the intelligentsia. This and other factors, such as the selective nature of emigration, which took especially those who preferred to live elsewhere than in communist Poland, made the group overrepresented, as it seems, in the Communist Party and state administration, their upper strata in particular. Moreover, popular perception tended to exaggerate the extent of this participation (not infrequently to paranoid proportions), following the well-rooted prejudice of żydokomuna or Jewish communism.

The real and imaginary Jews made part of the faction struggle inside the communist party. In the previous political crisis in Poland, in 1956, the leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) divided into two factions. The relatively reformist group included leading Jewish communists; the more conservative faction put the blame for Stalin-era crimes on the Jews. Władysław Gomułka, who after a few years of isolation returned to the top position in the party Politburo, allied with the first group, but then gradually marginalized its leaders and put his own people in key positions. In the 1960s a new force appeared on the political scene, the Partisans, a rather loose group of party leaders and lower-level activists united by similar political backgrounds (often in wartime underground, hence the name), unappeased ambitions, and a world view combining chauvinism and communism. Their leader was General Mieczysław Moczar, the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MSW) and its powerful secret services – the Security Service (SB).

Zionists and Zionism had been a target of communist hate propaganda for a long time. At least since the Slansky show trial in Czechoslovakia in 1952, the terms had become code names for Jews and Jewish, which allowed to attack the Jews in orthodox Leninist language. In Poland, after 1956 they disappeared from official discourse, yet were not forgotten. In particular, the theory of a Jewish threat to socialism had been ripening inside the MSW. Following the Israeli-Arab Six-Day War of June 1967, when the Soviet bloc states broke relations with Israel, it acquired a new dimension and dynamics. MSW leaders realized that the opportunity to hit the Zionists was near at hand. Speaking to the ministry directors on 28 June, General Moczar defined Polish Jews as infected with dangerous Zionism, indicated them as a collective object for particular scrutiny, and gave priority to the struggle against Zionism thus understood.

Preparations for a purge were well advanced when the ferment among students and intellectuals intensified in early 1968 and could easily be connected to it. Sources originating within the MSW begun to spread a theory of Jewish conspiracy behind the dissent.

After the riots had begun on 8 March the theme of Zionism was initially absent. But three days later two articles gave the signal and direction for a propaganda offensive. Meanwhile, the ‘Jewish explanation’ of the youth protests became part of the MSW secret reports to the Politburo. Taking them as a basis and side-tracking those Politburo members who opposed anti-Semitic initiatives in the past, Gomułka gave green light. From that point onwards the quantity and intensity of attacks against Zionism snowballed in the media and in public speeches. As head of the party Press Bureau Olszowski proudly explained, these followed the party order for “press campaign against the instigators and the bankrupt politicians, to reveal their political background—reactionary, revisionist, and Zionist forces”.

The communist party controlled virtually all the mass media. Olszowski noted with satisfaction that in just the first ten days of the campaign 250 relevant articles had appeared in the press. A significant portion of this propaganda barrage contained more or less openly antisemitic content. The 1968 campaign was also the first hate campaign in communist Poland to exploit the power of television, a new medium that had just become widespread. But most of the party energy went into organization of rallies against the Zionists and other enemies of Poland and socialism. Some were huge undertakings, with 100,000 people bused in from a whole province, but more people took part is smaller, local meetings: factory and department rallies, meetings of basic party organizations, sessions of county, city and district party committees, conferences of aktyw, meetings of the party satellite and ‘transmission belt’ organizations, such as trade unions, youth and women’s organizations, etc. In Warsaw alone, and in only the first two weeks of the campaign, there were more than 1,900 basic party meetings, nearly 400 rallies, 700 meetings of the aktyw, and 600 meetings of various party groups.

The slogans and banners at the gatherings were strikingly similar, following guidelines coming from the party headquarters. For example, the party chief in Poznan emphasized the “union of West German imperialism with Israeli [imperialism], which Zionist activity in our country is serving”, while his colleague in Kielce roared about “the international Zionist mafia”. Thousands of meetings passed resolutions and sent letters to the party leadership in an increasingly radical tone. “We swear in memory of those who died for power to the people, that we will clean from Polish soil, with our workers’ fists, all the instigators and leaders of the coup against the workers’ and peasants’ government. We will not permit revisionist and Zionist rioters to accuse us of antisemitism” – wrote the workers from the Polfer factories, while the workers from the Baildon steel works demanded “a purge of Zionist elements from party ranks, removal from their positions, and the refusal to permit their children to continue further university studies”.

Simultaneously grew a wave of dismissals from the party and jobs. It begun with Roman Zambrowski, once powerful member of the Politburo and Secretary of the party Central Committee. He was attacked in absentia, denied any chance to defend himself, removed from the party and his government position. News of the dismissal, broadcasted immediately, sent a clear message: if such a prominent figure was defenceless, any Zionist could be freely attacked. The dismissals descended from top government officials and editors-in-chief of major newspapers to university professors, bookkeepers in co-operatives, teachers in elementary schools, and factory foremen. Top-down instructions unleashed the social dynamics of the purge, fuelled by settling of personal accounts, desire to take someone’s position, popular resentment against the establishment and, last but not least, the hate of Jews.

A key moment of the campaign was March 19, when 3,000 party activists gathered in the Congress Hall in Warsaw to listen to Gomułka. They filled the hall holding banners such as ‘Down with the Agents of Imperialism and Reactionary Zionism!’ and ‘We Demand a Complete Unmasking and Punishment of the Political Instigators’. TV and radio channels broadcasted the meeting directly. Gomułka tried to appear moderate. He devoted to Zionism only a minor part of his speech and denied it was a real danger for Poland. There was, however—he claimed—a problem with those Jewish citizens of Poland who were attached more to Israel than to Poland. “I presume that Jews in this category will sooner or later leave our country”, he prophesied, adding: “We are ready to give emigration passports to those who consider Israel their Fatherland”. His speech contrasted with the audience’s behaviour, especially of the members of the Volunteer Reserve Militia (ORMO) in the gallery, who at that moment became excited and, holding aloft anti-Zionist banners, encouraged the speaker with shouts of “Bolder, bolder”, “Go ahead Wiesław, give names”.

Their behaviour made a greater impression on many of those who watching the meeting on TV than the words of Gomułka. “I will never forget this TV broadcast – reads a memoir. Watching the screen I saw faces marked with thirst for blood and cruelty”. Ida Kaminska, the famous actor and director of the Jewish Theatre, was shocked: “I barely managed to control myself, ran to the bedroom, took a pill, and with all my strength attempted to restrain my emotion, and screamed, “Let’s get out of here! Right away, or else I won’t survive”.

Unsurprisingly, Gomułka’s prophecy was self-fulfilling. Soon, hundreds and then thousands of people began submitting applications for emigration permits. Passports officers, instructed from the top, showed understanding to all Jews wishing to leave for Israel. A condition to get the permit was to renounce Polish citizenship. Consequently, the emigrants were leaving with a ‘travel document’, which made clear that “the bearer of this document is not a citizen of the People’s Republic of Poland”. It was a one-way ticket, with no return. The emigration wave culminated in 1969 and took almost 14,000 people, i.e. half of all the Jews in the country.

It is not easy to find evidence for specific motives of the officials and officers who made Zionists the target of the campaign. Lies were a key pillar of the regime, in particular of the 1968 campaign, and all those involved in starting the campaign had spent years in the school of distortion and disguise. Looking at their deeds, we see that the campaign served several goals.

First, the anti-Zionist campaign was a reaction to the student protests and dissent among intellectuals. It was a tool for fighting the youth rebellion, through compromising its alleged instigators, leaders, and goals as alien and perverse. The anti-Zionist propaganda also provided a smokescreen to hide the true target of police brutality. The symbolic anti- Jewish violence that filled the media blurred the fact that non-Jewish students and workers were the great majority of those beaten, arrested, and otherwise repressed.

Second, anti-Zionism was used to prevent the youth rebellion from spreading beyond the universities to broader groups, industrial workers in particular. This seems the most important motive for allowing and maintaining the aggressive and demagogic campaign. At least since the autumn of 1967, when a series of strikes followed a rise in food prices, the party leaders had been seriously concerned about the possible eruption of popular unrest. Portraying the dissident students and intellectuals as aliens—Jews, bloodstained Stalinists or their sons, arrogant members of the establishment, and so forth—certainly contributed to alienating them from the masses. Jewish communists seem to have been the best scapegoat available, against whom the party could direct popular frustration and anger for its past crimes, recent misdeeds, and constant absurdities of the regime. Pointing at Jewish communists, their Polish (ex-)comrades could absolve themselves and imply that after the purge, a better, purely Polish socialism would come.

The third objective of the campaign was to change the political balance in the party leadership. The attack on Zionists revitalized the conflict that had been ripening in the Politburo for a few years, and gave its proponents a strategic advantage over their adversaries, who were forced on the defensive and deprived of the support from the aktyw. Within a few weeks, the latter realized their defeat. The campaign enabled Gomułka to reconsolidate the party leadership on his terms and maintain his authoritarian rule for another two years. Gen. Moczar and his followers were successful in defeating their opponents and getting rid of thousands of Jews, but Gomułka skilfully outmanoeuvred them: he removed Moczar from his power base in the MSW to a formally higher and honourable but actually weaker position under his watchful eye.

Last but not least, we need to stress motivations of a different nature. Explaining why the Jews? we should not reduce the initiators and participants in the campaign to rational agents and their motivation to a calculated pursuit of interests. At least for some of them, attacking the Jews was a primary goal, a goal in itself, not just an instrument of other goals. Poland in spring 1968 was the scene of innumerable expressions of irrational anti-Jewish resentments and prejudices. They are well visible in the recorded words and deeds of the excited participants in the hate meetings, as well as some of the officials and officers at the upper levels of the state–party power structure. Making the Zionists a key target of the campaign served both the political interests and dark emotions, rooted in prejudice and paranoid worldview.